Contents

Objective

Install Nginx on your RedHat Linux distribution. Once installed, enable port 443 for HTTPS access to your web server. Create a Self-signed certificate to use for SSL. You can also use a free service like LetsEncrypt to get verified certs.

Installing Nginx

Add Nginx Repository

To add the CentOS 7 EPEL repository, open terminal and use the following command:

sudo yum install epel-release |

Install Nginx

Now that the Nginx repository is installed on your server, install Nginx using the following yum command:

sudo yum install nginx -y |

Start Nginx

Nginx does not start on its own. To get Nginx running, type:

sudo systemctl start nginx |

If you are running a firewall, run the following commands to allow HTTP and HTTPS traffic:

sudo firewall-cmd --permanent --zone=public --add-service=http sudo firewall-cmd --permanent --zone=public --add-service=https sudo firewall-cmd --reload |

You can do a spot check right away to verify that everything went as planned by visiting your server’s public IP address in your web browser (see the note under the next heading to find out what your public IP address is if you do not have this information already):

http://server_domain_name_or_IP/ |

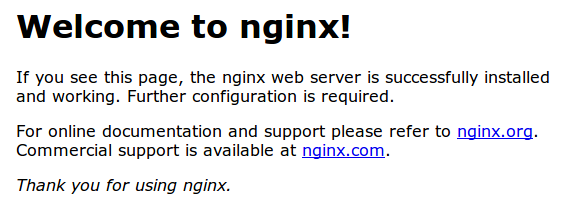

You will see the default CentOS 7 Nginx web page, which is there for informational and testing purposes. It should look something like this:

If you see this page, then your web server is now correctly installed.

Before continuing, you will probably want to enable Nginx to start when your system boots. To do so, enter the following command:

sudo systemctl enable nginx |

Congratulations! Nginx is now installed and running!

Server Root and Configuration

If you want to start serving your own pages or application through Nginx, you will want to know the locations of the Nginx configuration files and default server root directory.

Default Server Root

The default server root directory is /usr/share/nginx/html. Files that are placed in there will be served on your web server. This location is specified in the default server block configuration file that ships with Nginx, which is located at /etc/nginx/conf.d/default.conf.

Server Block Configuration

Any additional server blocks, known as Virtual Hosts in Apache, can be added by creating new configuration files in /etc/nginx/conf.d. Files that end with .conf in that directory will be loaded when Nginx is started.

Nginx Global Configuration

The main Nginx configuration file is located at /etc/nginx/nginx.conf. This is where you can change settings like the user that runs the Nginx daemon processes, and the number of worker processes that get spawned when Nginx is running, among other things.

Enabling SSL and Creating Self Signed Cert

Create the SSL Certificate

TLS/SSL works by using a combination of a public certificate and a private key. The SSL key is kept secret on the server. It is used to encrypt content sent to clients. The SSL certificate is publicly shared with anyone requesting the content. It can be used to decrypt the content signed by the associated SSL key.

The /etc/ssl/certs directory, which can be used to hold the public certificate, should already exist on the server. Let’s create an /etc/ssl/private directory as well, to hold the private key file. Since the secrecy of this key is essential for security, we will lock down the permissions to prevent unauthorized access:

sudo mkdir /etc/ssl/private sudo chmod 700 /etc/ssl/private |

Now, we can create a self-signed key and certificate pair with OpenSSL in a single command by typing:

sudo openssl req -x509 -nodes -days 365 -newkey rsa:2048 -keyout /etc/ssl/private/nginx-selfsigned.key -out /etc/ssl/certs/nginx-selfsigned.crt |

You will be asked a series of questions. Before we go over that, let’s take a look at what is happening in the command we are issuing:

- openssl: This is the basic command line tool for creating and managing OpenSSL certificates, keys, and other files.

- req: This subcommand specifies that we want to use X.509 certificate signing request (CSR) management. The “X.509” is a public key infrastructure standard that SSL and TLS adheres to for its key and certificate management. We want to create a new X.509 cert, so we are using this subcommand.

- -x509: This further modifies the previous subcommand by telling the utility that we want to make a self-signed certificate instead of generating a certificate signing request, as would normally happen.

- -nodes: This tells OpenSSL to skip the option to secure our certificate with a passphrase. We need Nginx to be able to read the file, without user intervention, when the server starts up. A passphrase would prevent this from happening because we would have to enter it after every restart.

- -days 365: This option sets the length of time that the certificate will be considered valid. We set it for one year here.

- -newkey rsa:2048: This specifies that we want to generate a new certificate and a new key at the same time. We did not create the key that is required to sign the certificate in a previous step, so we need to create it along with the certificate. The rsa:2048 portion tells it to make an RSA key that is 2048 bits long.

- -keyout: This line tells OpenSSL where to place the generated private key file that we are creating.

- -out: This tells OpenSSL where to place the certificate that we are creating.

- As we stated above, these options will create both a key file and a certificate. We will be asked a few questions about our server in order to embed the information correctly in the certificate.

The entirety of the prompts will look something like this:

Output Country Name (2 letter code) [AU]:US State or Province Name (full name) [Some-State]:Pennsylvania Locality Name (eg, city) []:State College Organization Name (eg, company) [Internet Widgits Pty Ltd]:HesserCAN Organizational Unit Name (eg, section) []:Main Common Name (e.g. server FQDN or YOUR name) []:server_IP_address Email Address []:mark@hessercan.com |

Both of the files you created will be placed in the appropriate subdirectories of the /etc/ssl directory.

While we are using OpenSSL, we should also create a strong Diffie-Hellman group, which is used in negotiating Perfect Forward Secrecy with clients.

We can do this by typing:

sudo openssl dhparam -out /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem 2048 |

This may take a few minutes, but when it’s done you will have a strong DH group at /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem that we can use in our configuration.

Configure Nginx to Use SSL

The default Nginx configuration in CentOS is fairly unstructured, with the default HTTP server block living within the main configuration file. Nginx will check for files ending in .conf in the /etc/nginx/conf.d directory for additional configuration.

We will create a new file in this directory to configure a server block that serves content using the certificate files we generated. We can then optionally configure the default server block to redirect HTTP requests to HTTPS.

Create the TLS/SSL Server Block

Create and open a file called ssl.conf in the /etc/nginx/conf.d directory:

sudo vi /etc/nginx/conf.d/ssl.conf |

Inside, begin by opening a server block. By default, TLS/SSL connections use port 443, so that should be our listen port. The server_name should be set to the server’s domain name or IP address that you used as the Common Name when generating your certificate. Next, use the ssl_certificate, ssl_certificate_key, and ssl_dhparam directives to set the location of the SSL files we generated:

server { listen 443 http2 ssl; listen [::]:443 http2 ssl; server_name server_IP_address; ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/certs/nginx-selfsigned.crt; ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private/nginx-selfsigned.key; ssl_dhparam /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem; } |

Next, we will add some additional SSL options that will increase our site’s security. The options we will use are recommendations from Remy van Elst on the Cipherli.st site. This site is designed to provide easy-to-consume encryption settings for popular software. You can learn more about his decisions regarding the Nginx choices by reading Strong SSL Security on nginx.

There are a few pieces of the configuration that you may wish to modify. First, you can add your preferred DNS resolver for upstream requests to the resolver directive. We used Google’s for this guide, but you can change this if you have other preferences.

Finally, you should take a moment to read up on HTTP Strict Transport Security, or HSTS, and specifically about the “preload” functionality. Preloading HSTS provides increased security, but can have far reaching consequences if accidentally enabled or enabled incorrectly. In this guide, we will not preload the settings, but you can modify that if you are sure you understand the implications.

server { listen 443 http2 ssl; listen [::]:443 http2 ssl; server_name server_IP_address; ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/certs/nginx-selfsigned.crt; ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private/nginx-selfsigned.key; ssl_dhparam /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem; ######################################################################## # from https://cipherli.st/ # # and https://raymii.org/s/tutorials/Strong_SSL_Security_On_nginx.html # ######################################################################## ssl_protocols TLSv1 TLSv1.1 TLSv1.2; ssl_prefer_server_ciphers on; ssl_ciphers "EECDH+AESGCM:EDH+AESGCM:AES256+EECDH:AES256+EDH"; ssl_ecdh_curve secp384r1; ssl_session_cache shared:SSL:10m; ssl_session_tickets off; ssl_stapling on; ssl_stapling_verify on; resolver 8.8.8.8 8.8.4.4 valid=300s; resolver_timeout 5s; # Disable preloading HSTS for now. You can use the commented out header line that includes # the "preload" directive if you understand the implications. #add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=63072000; includeSubdomains; preload"; add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=63072000; includeSubdomains"; add_header X-Frame-Options DENY; add_header X-Content-Type-Options nosniff; ################################## # END https://cipherli.st/ BLOCK # ################################## } |

Because we are using a self-signed certificate, the SSL stapling will not be used. Nginx will simply output a warning, disable stapling for our self-signed cert, and continue to operate correctly.

Finally, add the rest of the Nginx configuration for your site. This will differ depending on your needs. We will just copy some of the directives used in the default location block for our example, which will set the document root and some error pages:

server { listen 443 http2 ssl; listen [::]:443 http2 ssl; server_name server_IP_address; ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/certs/nginx-selfsigned.crt; ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private/nginx-selfsigned.key; ssl_dhparam /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem; ######################################################################## # from https://cipherli.st/ # # and https://raymii.org/s/tutorials/Strong_SSL_Security_On_nginx.html # ######################################################################## . . . ################################## # END https://cipherli.st/ BLOCK # ################################## root /usr/share/nginx/html; location / { } error_page 404 /404.html; location = /404.html { } error_page 500 502 503 504 /50x.html; location = /50x.html { }} |

When you are finished, save and exit. This configures Nginx to use our generated SSL certificate to encrypt traffic. The SSL options specified ensure that only the most secure protocols and ciphers will be used. Note that this example configuration simply serves the default Nginx page, so you may want to modify it to meet your needs.

(Optional) Create a Redirect from HTTP to HTTPS

With our current configuration, Nginx responds with encrypted content for requests on port 443, but responds with unencrypted content for requests on port 80. This means that our site offers encryption, but does not enforce its usage. This may be fine for some use cases, but it is usually better to require encryption. This is especially important when confidential data like passwords may be transferred between the browser and the server.

The default Nginx configuration file allows us to easily add directives to the default port 80 server block by adding files in the /etc/nginx/default.d directory. Create a new file called ssl-redirect.conf and open it for editing with this command:

sudo vi /etc/nginx/default.d/ssl-redirect.conf |

Then paste in this line:

return 301 https://$host$request_uri/; |

Save and close the file when you are finished. This configures the HTTP on port 80 (default) server block to redirect incoming requests to the HTTPS server block we configured.

Enable the Changes in Nginx

Now that we’ve made our changes, we can restart Nginx to implement our new configuration.

First, we should check to make sure that there are no syntax errors in our files. We can do this by typing:

sudo nginx -t |

If everything is successful, you will get a result that looks like this:

nginx: [warn] "ssl_stapling" ignored, issuer certificate not found nginx: the configuration file /etc/nginx/nginx.conf syntax is ok nginx: configuration file /etc/nginx/nginx.conf test is successful |

Notice the warning in the beginning. As noted earlier, this particular setting throws a warning since our self-signed certificate can’t use SSL stapling. This is expected and our server can still encrypt connections correctly.

If your output matches the above, your configuration file has no syntax errors. We can safely restart Nginx to implement our changes:

sudo systemctl restart nginx |

The Nginx process will be restarted, implementing the SSL settings we configured.

Test Encryption

Now, we’re ready to test our SSL server.

Open your web browser and type https:// followed by your server’s domain name or IP into the address bar:

https://server_domain_or_IP |

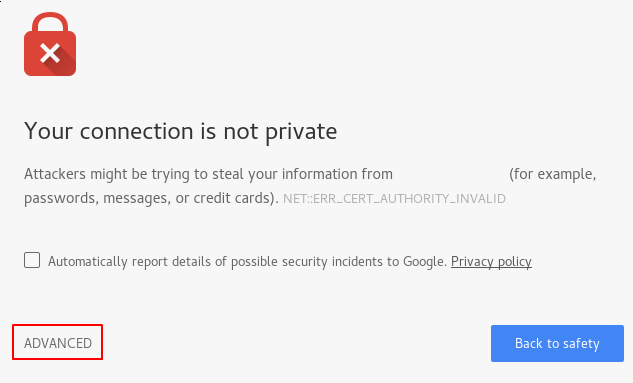

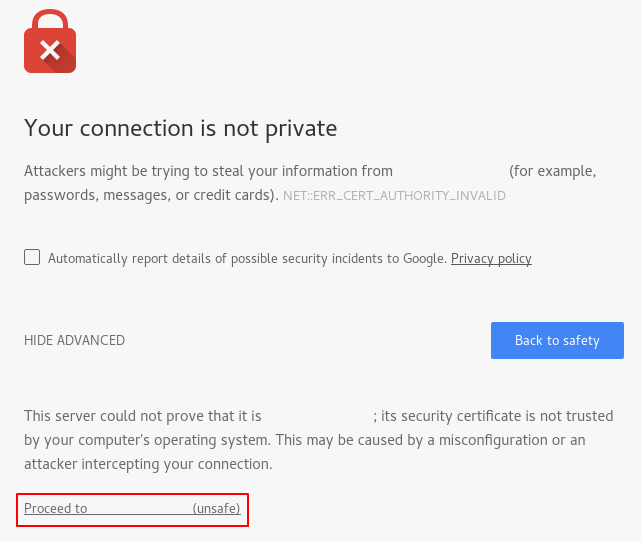

Because the certificate we created isn’t signed by one of your browser’s trusted certificate authorities, you will likely see a scary looking warning like the one below:

This is expected and normal. We are only interested in the encryption aspect of our certificate, not the third party validation of our host’s authenticity. Click “ADVANCED” and then the link provided to proceed to your host anyway:

You should be taken to your site. If you look in the browser address bar, you will see some indication of partial security. This might be a lock with an “x” over it or a triangle with an exclamation point. In this case, this just means that the certificate cannot be validated. It is still encrypting your connection.

If you configured Nginx to redirect HTTP requests to HTTPS, you can also check whether the redirect functions correctly:

http://server_domain_or_IP |

If this results in the same icon, this means that your redirect worked correctly.

Conclusion

You have configured your Nginx server to use strong encryption for client connections. This will allow you serve requests securely, and will prevent outside parties from reading your traffic.